So-called DiGA (digital health applications) can be reimbursed by statutory health insurance companies. This became possible for the first time when the Digital Supply Act (DVG) came into force on December 19, 2019. However, not every health app or medical software meets the definition of a DiGA and is therefore eligible for reimbursement. In this article, we explain in detail which criteria your app or software must meet in order to be considered a DiGA.

Update to the DiGA guidelines on December 10, 2025: The official DiGA guidelines have been updated to version 3.6 and contain numerous additions relating to the decision “Is your application a DiGA?” (qualification). The new features have already been incorporated into the technical article below. An overview of the changes to the guidelines can be found here: Overview of all changes

Table of Contents

- 1. Overview of DiGA Criteria

- 1.1 Criterion #1: Medical Device with a lower or higher Risk Class

- 1.2 Criterion #2: Positive supply effect, consistent with the intended purpose of the medical device

- 1.3 Criterion #3: Primary digital function

- 1.4 Criterion #4: More than just device control

- 1.5 Criterion #5: Diagnosis or treatment of diseases or injuries

- 1.6 Criterion #6: No pure (primary) prevention

- 1.7 Criterion #7: The user is the patient

- 1.8 Criterion #8: Individualization

- 1.9 Criterion #9: Excluded services

- 1.10 Criterion #10: Publication prior to application

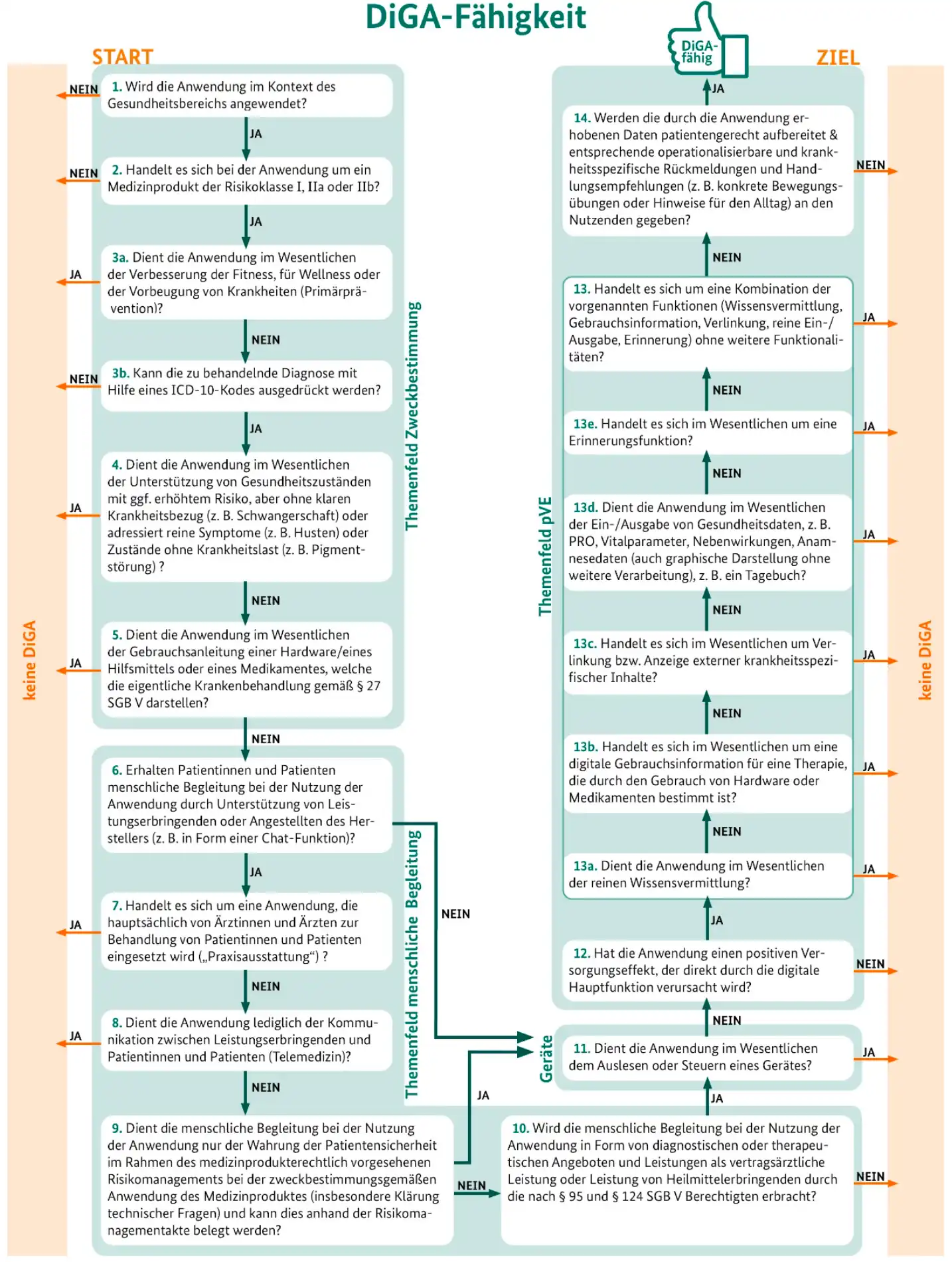

- 2. The DiGA Capability Decision Tree

- 3. Requirements for Fulfilling the Criteria

- 4. Selective Contracts – an Alternative to DiGA

- 5. Conclusion

1. Overview of DiGA Criteria

The official DiGA guidelines issued by the BfArM succinctly summarize the definition of DiGA. In order for your product to be potentially eligible for reimbursement as a DiGA, it must meet the following criteria.

1.1 Criterion #1: Medical Device with a lower or higher Risk Class

Your product must be a medical device be in a lower or higher risk class (I, IIa, or IIb).

Of course, not all software is a medical device. For example, an app whose purpose is purely to document medical data is not a medical device and therefore not a DiGA. If your app collects blood pressure values but does not evaluate them for the diagnosis or treatment of diseases, it is not a medical device. You can find more information in our article on “Is your app a medical device?”.

Is your app a medical device? Great! However, it is still unclear whether it is also a medical device in a low or higher risk class (I, IIa or IIb).

Rule 11 of the MDR is particularly relevant for determining the risk class. We have also written a detailed guide on this topic: Practical guide to determining the risk class for software products

1.2 Criterion #2: Positive supply effect, consistent with the intended purpose of the medical device

The main digital function of the DiGA must be consistent with the intended purpose of the underlying medical device. Functions that are part of fulfilling the medical purpose must also constitute the functional scope of the DiGA.

The following aspects, among others, are relevant here:

- Excluding DiGA functions: Sometimes a DiGA has certain functions that manufacturers would prefer not to subject to the strict requirements of the DiGA Regulation. Some functions make it difficult or impossible, for example, to obtain BSI security certification for the DiGA or to prove its positive effect on care. Nevertheless, if these functions serve to fulfill the intended purpose of the medical device, you may not exclude them from the scope of the DiGA. This means that you may not exclude any functions from the scope of your DiGA, even if this makes it more difficult or prevents you from obtaining initial DiGA approval.

- Inconsistency with intended purpose: Another form of inconsistency between the intended purpose of the medical device and the main function of the DiGA would be as follows: Your DiGA targets a different medical indication than the underlying medical device. Your medical device is used to treat knee joint osteoarthritis, but your DiGA has wrist joint osteoarthritis as its main function. This would be an inconsistency in this sense and would not qualify as a DiGA.

1.3 Criterion #3: Primary digital function

By definition, your product must be based primarily on digital technologies. This excludes, for example, a blood pressure monitor itself being a DiGA. Hardware is not a DiGA.

But even if your product is, for example, an app or web application and therefore seemingly completely digital, you should note the following:

- Hardware integration: If you connect hardware to your app via Bluetooth, for example, the positive healthcare effect of your DiGA must not be attributable to the use of the hardware. The positive healthcare effect must be based on the main digital function (e.g., digital exercise program) and thus be independent of the hardware.

- Involvement of practitioners: The positive care effect must not be achieved through the involvement of, for example, a physician. If your DiGA only “works” when a doctor gives personal therapy recommendations via video calls, then this is not a primary digital function of your DiGA. The DiGA must not depend on this human component for the positive effect on care. This must be optional and, ideally, deactivated in the intervention group when conducting the DiGA study.

1.4 Criterion #4: More than just device control

Your app must fulfill the medical purpose essentially through the main digital function. If your app only serves to control a medical device – and therefore does not provide the essential medical purpose itself – it is not a DiGA. Although a DiGA can communicate with medical devices and read out sensor data, for example, this must not be the main purpose.

If your app reads external sensor data from a medical device and makes a diagnosis or gives treatment recommendations on this basis, this criterion is met. The essential purpose in this case is diagnosis or therapy improvement, and the purpose is fulfilled by a digital algorithm in your app/software.

1.5 Criterion #5: Diagnosis or treatment of diseases or injuries

A DiGA is defined as an application that supports the “detection, monitoring, treatment, or alleviation of diseases or the detection, treatment, alleviation, or compensation of injuries or disabilities.” This means that, for example, contraceptive apps, cycle tracking apps or pure (primary) prevention apps (criterion #5) are not DiGA. An application that supports patients with diagnosed visual impairment with digital visual exercises during therapy, for example, fulfills this criterion and could therefore also be a DiGA.

1.6 Criterion #6: No pure (primary) prevention

The DiGA guidelines put it as follows: The prerequisite is that there is a risk factor in the sense of a disease that can be coded as a diagnosis.

An app that helps a healthy person to prevent illness is not a DiGA. (Primary) prevention apps are also potentially medical devices, but not yet DiGAs. This is because a DiGA is prescribed by a doctor in the case of a disease diagnosis, for example, and is therefore always aimed at people with a specific indication (ICD-10 code).

1.7 Criterion #7: The user is the patient

An app that primarily supports doctors in their daily work is not a DiGA. A DiGA must be intended for use by the patient. The app can certainly involve the doctor as long as the patient remains the main user.

1.8 Criterion #8: Individualization

DiGA must generate individualized feedback based on patient input.

Example: Your DiGA asks about the patient’s state of health in an onboarding questionnaire. The patient then receives a consistent selection of knowledge content and exercises.

This would most likely not meet the individualization criterion. Instead, the knowledge content and exercises should be prepared based on the values entered. For example, you could display different knowledge content and exercises to patients with different degrees of severity or stages of the disease. This allows you to individualize the digital health application based on the data entered.

1.9 Criterion #9: Excluded services

The DiGA does not cover services that are excluded under Chapter III of SGB V. Likewise, it may not contain any content that has already been rejected by the Joint Federal Committee in accordance with Sections 92, 135, or 137c.

1.10 Criterion #10: Publication prior to application

The DiGA must already be available at the time of application. It must be published in the relevant app stores or, in the case of a web application, be publicly accessible via the designated website.

2. The DiGA Capability Decision Tree

In version 3.6 of the DiGA guidelines, the BfArM has included a clear diagram to help you qualify your application as a DiGA:

Figure 3 from the DiGA guidelines: DiGA capability decision tree. Source: BfArM.

Further information on all criteria and requirements can be found in the official DiGA guidelines published by the BfArM.

3. Requirements for Fulfilling the Criteria

Of course, even if your software meets these criteria, it will not automatically be included in the DiGA directory and reimbursed. If you basically meet each of these criteria, the next step is to look at the requirements for DiGA. These requirements are regulated by the Digital Health Applications Ordinance (DiGAV). These are then explained in more detail in the official DiGA guidelines.

The requirements include, on the one hand, the “requirements for security, functionality, data protection and security, and the quality of digital health applications.” In summary, this point includes the following requirements:

- Safety and functionality requirements

- Data protection and data security requirements

- Quality and interoperability requirements

- Robustness requirements

- Consumer protection requirements

- User-friendliness requirements

- Requirements for the support of service providers

- Requirements for the quality of medical content

- Patient safety requirements

You must also demonstrate a positive supply effect with your DiGA. According to the DVG, a positive care effect is either a medical benefit or patient-relevant structural and procedural improvements in care. You must prove this positive supply effect in scientific studies. If you do not have such studies available at the time of application, you must at least submit a scientific evaluation concept with which you would like to demonstrate the effects of care at a later date.

Furthermore, you must obtain data security certification from the BSI, for example, and connect your DiGA to the electronic patient record.

4. Selective Contracts – an Alternative to DiGA

If your digital solution does not qualify as a DiGA, there is also the option in Germany of concluding selective contracts with individual health insurance companies. This provides you with a route to reimbursement that is tailored to your application.

In our guide to selective contracts, we provide an overview of this alternative form of cost reimbursement: To the guide – Selective contracts for digital solutions

Even beyond selective contracts and DiGA, there are other ways to obtain reimbursement for software products:

- Overview of all paths to reimbursement: Read our white paper

- Reimbursement for software in the GKV medical aids directory (HMV): See our guide

- Digital care applications – DiPA procedure: To our guide

- Central Prevention Review Board (ZPP): About our guidelines

In addition to the aforementioned reimbursement options, it is also worth looking into public funding opportunities that can bridge the gap. First and foremost, it is worth taking a look at the G-BA’s Innovation Fund, which provides financial support for digital healthcare solutions in their early stages.

You can find more information in our guide to the Innovation Fund: Go to guide

5. Conclusion

Whether your app is potentially a DiGA is defined by the criteria mentioned. However, the devil is often in the details. You should therefore read the official DiGA guidelines carefully when planning and learn from the experiences of other DiGA manufacturers. Even though the DiGA guidelines are comprehensive and certainly offer a lot of help, there is unfortunately still a lot of implicit knowledge among existing DiGA manufacturers that has not yet been included there.

QuickBird Medical has been developing DiGA on a contract basis since its inception. As of today (2025), we have already implemented over 15 DiGA projects. If you are planning a DiGA and would like to outsource the development and regulatory aspects to a service provider, please feel free to contact us.