“Clinical evaluation? No problem!”

“A doctor was recently interviewed in the Süddeutsche Zeitung! She clearly stated that mindfulness apps help with depression. We can refer to that, can’t we?”

Unfortunately, it’s not that simple. Of course, our exaggerated example would not convince the supervisory authority or a notified body, because the Medical Device Regulation (MDR) requires detailed clinical evidence for medical devices. Of course, software medical devices are not exempt from this.

In this article, you will find out which documents you need to create and how you can avoid the spectre of a clinical trial.

Good to know:

In this article (as in the MDR), a distinction is made between two terms: clinical evaluation and clinical investigation. The clinical evaluation comprises the entire collection of clinical evidence for a medical device. This includes the planning of the search for clinical data, its implementation and regular updating. The clinical trial, on the other hand, is an important source of clinical evidence – and in most cases involves a great deal of effort, as you have to conduct your own study.

Focus of this article

The article focuses on the clinical evaluation of medical devices according to MDR. The main focus is on software medical devices, but most of the content is also transferable to other medical devices. We will also tell you how, in the best case scenario, you can even do without a clinical trial.

The information in this article is taken from the MDR, MEDDEV 2.7/1 revision 4 and various MDCG guidance documents and is summarized here.

In addition, in Chapter 5 we take a look into the future and briefly discuss the new draft standard ISO 18969, which, as an upcoming international standard, is intended to harmonize clinical evaluation across the entire product life cycle.

Contents

- 1. Purpose of the clinical evaluation

- 2. What documents does the MDR require?

- 3. Do I need to conduct a clinical evaluation (even for Class I devices)?

- 4. Do I have to prepare the clinical evaluation myself?

- 5. A look into the future: The new ISO 18969

- 6. Helpful resources

- 7. Conclusion

1. Purpose of the clinical evaluation

The fundamental objective of clinical evaluation is to prove that a medical device fulfills the intended purpose defined by the manufacturer. The stated performance and safety requirements are to be verified and undesirable side effects excluded.

To some extent, this objective also coincides with risk management, which involves analyzing potential hazards emanating from the product. If you like, the symbiosis of risk management and clinical evaluation takes place in the risk-benefit assessment.

A sound clinical evaluation is necessary so that the residual risks can be compared and evaluated against the evidence-based benefits.

2. What documents does the MDR require?

If you have been dealing with medical device regulations for a while, it is nothing new that almost everything a manufacturer does must also be documented.

The MDR also has clear specifications for clinical evaluation as to which documents must be created and maintained by the manufacturer. However, some of these requirements are very abstract and are supplemented by a handful of guidance documents (e.g., MDCG).

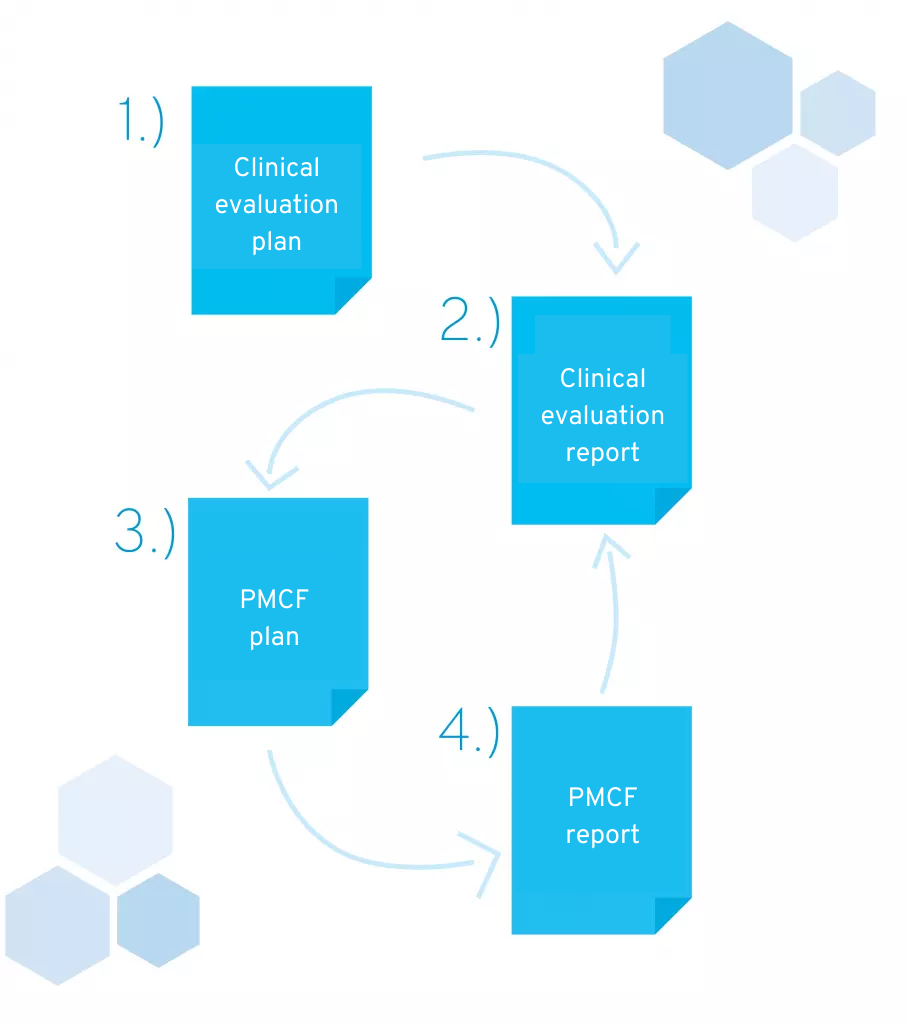

In this chapter, we would like to explain the contents of the four documents that must be included in your technical documentation:

- Clinical evaluation plan (CEP)

- Clinical Evaluation Report (CER)

- Post-market clinical follow-up plan (PMCF plan)

- Post-market clinical follow-up report (PMCF report)

Documents required for technical documentation in accordance with MDR

2.1 Clinical evaluation plan

The clinical evaluation plan is the first document created in the course of the clinical evaluation. As the name suggests, it describes the planned activities during the clinical evaluation, as well as instructions for searching for clinical data and criteria for its evaluation.

Let’s take a look at the individual requirements of the MDR for the clinical evaluation plan to get a clearer picture of the information that must be included. These can be found in Annex XIV, Part A, Section 1, Letter a) of the MDR. Below, we list each of the requirements for a clinical evaluation plan mentioned there and briefly discuss them:

“Determination of the essential safety and performance requirements, which must be substantiated with relevant clinical data;”

- Take a look at Annex I of the MDR to identify the essential safety and performance requirements for your product. Then check for which requirements clinical data is still needed. The basic safety and performance requirements describe all the requirements that a medical device must fulfill. Examples of this are specifications for chemical composition and labeling. As you can already see, not every requirement applies to every product. Many requirements cannot be applied to pure software products. For example, it is obvious that issues such as “chemical, physical, and biological properties” or “protection against radiation” are of little relevance to software code. Other requirements, however, such as sufficient accuracy of measurement functions or the ability to fulfill the intended purpose when used by laypersons, could be substantiated for software products by clinical data.

“Specification of the intended purpose of the product;”

- You have probably already written a purpose statement for your product. If not, you should deal with it as soon as possible! You will come across the intended purpose even more frequently when developing a medical device. Among other things, this is also the decisive factor when it comes to determining the risk class and defines the purpose of your product. An early definition therefore not only helps with clinical evaluation. You can find instructions on phrasing the intended purpose in this article: Phrasing of the intended purpose for (software) medical devices

“Precise specification of the intended target groups with clear indications and contraindications;”

- This point is almost self-explanatory, but when specifying the target groups, also consider different user groups. For example, your software is used by medical professionals and not just by patients. In addition to the indication, it can also be helpful to use other parameters to narrow down the target group (e.g. age, language skills, etc.). Also consider the list in Appendix A3 of MEDDEV-2.7/1 revision 4 to identify relevant inclusion criteria.

“Detailed description of the intended clinical benefit for patients, with relevant specific parameters for the clinical outcome;”

- The MDR defines clinical benefit as follows: “Clinical benefit” means the positive effects of a product on a person’s health, as demonstrated by meaningful, measurable, and patient-relevant clinical outcomes, including diagnostic outcomes, or a positive impact on patient management or public health.

- One clinical benefit could therefore be that a person’s quality of life improves. The second step is to ask how this benefit can be measured. On the one hand, you need to define what clinical benefit your product is aiming for and how you plan to demonstrate this benefit. Appendix 7.2 of MEDDEV-2.7/1 revision 4 provides additional input in this regard.

- The clinical benefit describes the expected performance of a product, which is derived from the intended purpose. It has the property that it must be clearly observable. Therefore, you should specify concrete, measurable factors here, such as “reduction of depressive symptoms” or “improvement in quality of life.”

“Specification of the methods to be used for assessing the qualitative and quantitative aspects of clinical safety, with clear reference to the determination of residual risks and side effects;”

- Methods used to evaluate the clinical safety of the product, in particular residual risks and side effects. The decisive factor here is the evaluation of the clinical data found. This includes which databases you want to search, which search filters you use and which criteria you use to evaluate the sources found. For example, your document should show that a randomized controlled trial is more meaningful than an expert interview. Chapter 9.3.2. MEDDEV-2.7/1 revision 4 provides helpful information for evaluating the relevance of sources. An exciting list of evaluation criteria for studies can be found in Appendix 6 of this document. This includes, for example, the sample size and the disclosure of the methods used.

“Non-exhaustive list and specification of parameters for determining the acceptability of the benefit-risk ratio for the various indications and the intended purpose or purposes of the product, based on the latest medical knowledge;”

- The parameters are specified here in order to assess the justifiability of the risk-benefit ratio. It is important to take the current state of medical knowledge into account and also consider the effectiveness and risks of other methods.

“Information on how questions regarding the risk-benefit ratio for certain components, such as the use of pharmaceutical, non-viable animal or human tissue, are to be clarified […];”

- This point can be ignored by software manufacturers.

“Clinical development plan: from exploratory studies, such as first-in-human studies, feasibility studies, and pilot studies, to confirmatory studies, such as pivotal clinical trials, and post-marketing clinical monitoring in accordance with Part B of this Annex, specifying milestones and describing possible acceptance criteria;”

- The clinical development plan includes all steps planned to collect and generate clinical data. This refers in particular to scientific studies that you are planning for your product.

- The clinical development plan also specifies planned clinical trials and refers to the relevant documents.

- A planned literature search is also shown under this item.

If you plan to conduct the clinical evaluation with reference to one or more similar products, you can already list the products that will be tested for similarity in this plan. The similarity is demonstrated in the clinical evaluation report.

2.2 Clinical evaluation report

After the clinical evaluation plan describes the central procedure for the clinical evaluation, the report contains all the resulting data used for the clinical evaluation. It results, so to speak, from the clinical evaluation plan and contains a statement as to whether your product fulfills its intended purpose and basic safety and performance requirements (you can find guidance on formulating your intended purpose in this article).

Specifically, your clinical evaluation report should meet the following requirements (Appendix A10, MEDDEV-2.7/1 revision 4):

- The report must be understandable for third parties and summarize the clinical data in such a way that your statements and conclusions are comprehensible.

- The data generated by the manufacturer (e.g. results of a clinical trial) must be summarized and referenced.

- When compared with similar products:

- The similarity of both products must be described in a comprehensible manner.

- All differences between your product and the similar product must be described. In addition, you need an explanation as to why the products are nevertheless to be regarded as similar.

- The current state of the art must be fully summarized and supported by literature. State-of-the-art? Yet another term where the MDR leaves us in the lurch with a clear definition. Fortunately, there is a more detailed specification in ISO 14971, according to which the state of the art comprises the current and generally recognized good practice in technology and medicine. It does not therefore refer to the most technologically and scientifically advanced methods, but to those products, treatment methods, etc. that are already used in practice and available on the market.

- The report must include an explanation of why the risk-benefit ratio is acceptable in relation to the state of the art.

- If your product is available in multiple versions, you must declare that the clinical data is sufficient for all variants and user groups.

- Compliance with all applicable safety and performance requirements must be confirmed.

- The report must include a statement confirming that the information material you have provided corresponds to the contents of the report.

- All remaining risks and unanswered questions must be listed. These must then be addressed in post-market surveillance.

- The report must be dated and contain the CVs (or other proof of qualifications) of the persons involved. You also need a declaration of interest from all parties involved. It is best to have everyone sign the final report.

2.3 Post-market clinical follow-up (plan and report)

The clinical evaluation prior to a product’s market entry is only a snapshot and reflects the current state of knowledge—which, as we know, is subject to change. For example, doctors no longer perform bloodletting and refrain from prescribing cigarettes to patients with headaches. However, these measures were once part of the current state of medical knowledge. The serious consequences of this were only recognized over time.

As a manufacturer of a medical device, you must therefore ensure that new findings from research and specifically related to your product are discovered—and for this purpose, the MDR prescribes “post-market clinical follow-up.” This is abbreviated as PMFC.

The PMCF describes the continuous collection and analysis of clinical data associated with your product. Here, too, you should draw up a plan and a report.

The PMCF plan is derived from the clinical evaluation plan and the open questions and uncertainties identified in the clinical evaluation report. Similar to the clinical evaluation plan, it describes the planned activities in the PMCF phase, and much of its content can be adopted verbatim.

This includes, for example:

- Literature research in scientific databases

- Search of safety databases (e.g. BfArM safety database)

- Evaluation of user feedback

- Conducting studies on the product

The PMCF plan also defines the interval at which these activities take place. In each cycle, a PMCF report is then created, documenting the respective results and describing their impact on the clinical evaluation report.

Important: Relevant findings from the PMCF report are integrated into the clinical evaluation report. This means that external parties should be able to find all the information about the product in this clinical evaluation report at any time – from the initial evaluation to the last PMCF cycle.

The MDCG provides valuable templates for PMCF documents that you can use as a guide: MDCG 2020-7 for the plan and MDCG 2020-8 for the report.

Difference between PMCF and post-market surveillance

In practical terms, the PMCF is part of post-market surveillance (PMS). PMS is primarily about continuously monitoring whether a medical device fulfills its intended purpose and is safe. Relevant information can come from various sources, such as direct user feedback or the analysis of usage data. If your PMCF is based solely on literature, it can be considered a subset of PMS. A distinction between the two terms is particularly useful if clinical trials and other studies are also conducted in the course of the PMCF.

3. Do I need to conduct a clinical evaluation (even for Class I devices)?

Yes, a clinical evaluation must be performed in all cases and is mandatory for all medical devices, including those in risk class I.

However, the effort required for the clinical evaluation can vary considerably. If you divide the clinical evaluation into individual work packages, you quickly realize that there is one particularly large block – the clinical trial.

MDR definition: “Clinical trial” means a systematic investigation involving one or more human subjects, conducted for the purpose of evaluating the safety or performance of a device.

Specifically, the clinical trial is a scientific study that must be registered with the BfArM. It is clear that this is often associated with enormous costs and considerable time expenditure. However, the whole thing can even be avoided under certain circumstances. If there is a so-called similar medical device that is so similar to your product that you can also refer to the data of this product, you can avoid the clinical trial. In concrete terms, this can mean a time saving of several months – not to mention the costs.

3.1 How to find similar products under the MDR

You are probably like most manufacturers and are asking yourself whether there is a suitable product in your case that is already on the market as a medical device and to whose clinical data you have access. But how do you find out whether there is a similarity?

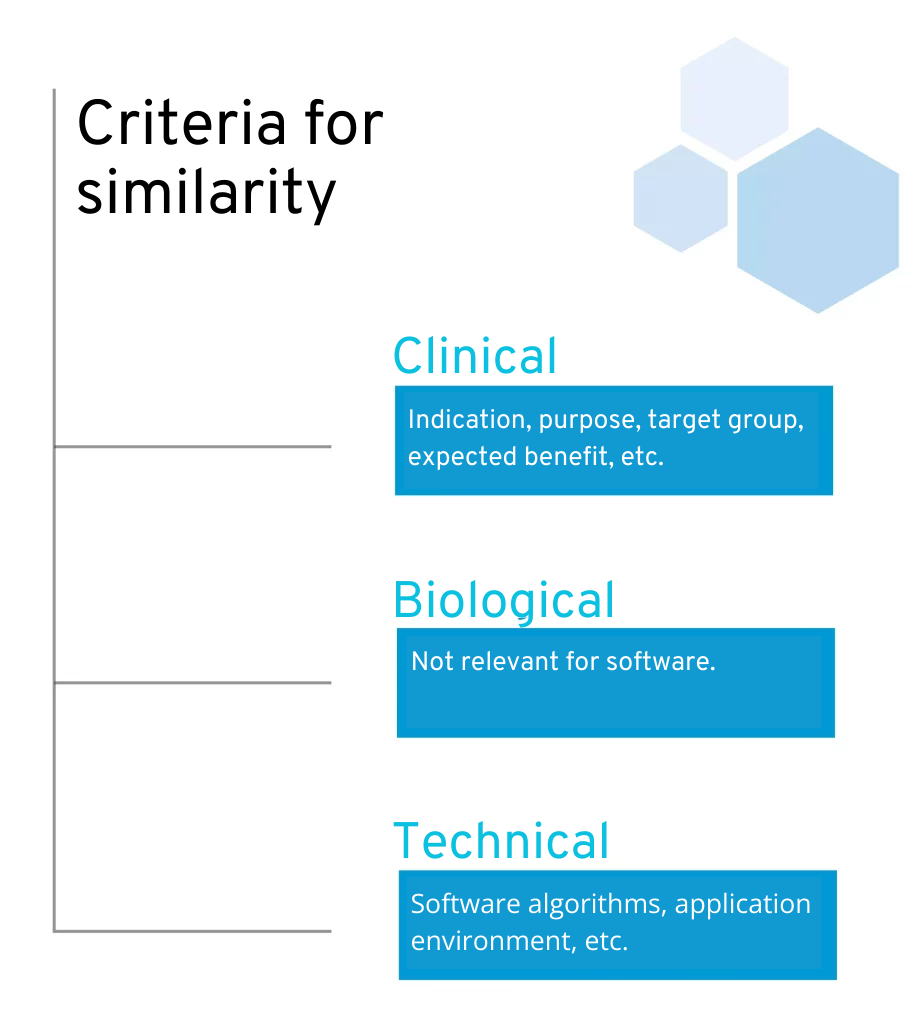

To this end, the MDR specifies concrete criteria for comparing the similarity of two products:

Technical: The product is of similar design, is used under similar conditions of use, has similar specifications and characteristics including […] software algorithms, uses similar deployment methods where applicable, and has similar operating principles and critical performance requirements.

Biological: Is irrelevant for software.

Clinical: The device is used under the same clinical condition or for the same clinical purpose, including a similar severity and stage of disease, on the same body site and in similar patient populations in terms of, inter alia, age, anatomy and physiology, has the same users and performs similarly, substantially and decisively in terms of the expected clinical effect for a specific intended purpose.

Criteria for similarity according to MDR

This leaves two points for software manufacturers:: clinical and technical equivalence. Clinical similarity is comparatively easy to verify. A look at the intended use or operating instructions of other applications should already provide good information here. Depending on the stage of development of their own product, manufacturers can, for example, make adjustments to their product or the target group in order to ensure similarity. This can be particularly useful for an initial market entry.

However, it becomes more difficult when examining technical similarity. One of the crucial points here is the evaluation of the software algorithms. But to what extent is an algorithm defined as “similar”? Do two algorithms have to have exactly the same software code to be similar? Is the evaluation of two questionnaires similar if a sum score is calculated for both, even if the content of the questions differs? Is the algorithm for controlling a blood pressure monitor similar to that for controlling a device from another manufacturer?

Questions upon questions that are difficult to answer on the basis of the information available. At least there is a more detailed explanation of this in the MDCG 2020-5, which also contains a helpful table in Appendix I. This states that when comparing software algorithms, the primary focus should be on the functional principles and intended purpose. Fortunately, according to MDCG, it is not necessary to prove equivalence of the software code.

Quote from the MDCG 2020-5: “It is the functional principle of the software algorithm, as well as the clinical performance(s) and intended purpose(s) of the software algorithm, that shall be considered when demonstrating the equivalence of a software algorithm. It is not reasonable to demand that equivalence is demonstrated for the software code, provided it has been developed in line with international standards for safe design and validation of medical device software.” – Attention: The MDCG documents and their interpretations of the MDR are not legally binding. However, they are probably the most valid source for implementing the MDR requirements.

An important note at this point: If you are referring to a similar product, you must also have appropriate access to the associated clinical data. It is best to first search scientific databases for relevant publications or contact the manufacturer directly. One relevant point of contact is the German Clinical Trials Registry (DRKS). The DRKS is the central register for clinical trials in Germany and you can also find studies on medical devices there.

3.2 If you cannot find a similar product

If you cannot find a similar product, there is unfortunately only one answer: you have to bite the bullet and carry out a clinical trial. There is an exception if you can justify on the basis of MDR, Article 61, sentence (10) that evidence based on clinical data is unsuitable for your product.

4. Do I have to prepare the clinical evaluation myself?

In principle, the clinical evaluation is part of the technical documentation for your product, which you as the manufacturer must create and maintain on an ongoing basis. Even though you can outsource the creation process, in most cases you can do it yourself—even if you have limited prior knowledge.

Even start-ups often already have clinical experts (physicians or other people with a scientific background) on board who have a basic understanding of clinical trials. You will benefit from conducting a clinical evaluation in that you and your team will better understand your market and your target group by reading clinical studies. You will gain scientific insight into effective and potentially ineffective methods and, even after the product has been placed on the market, you will know exactly what to look out for and what data will be relevant in the future.

When carrying out a clinical evaluation, a certain scientific understanding is important in order to be able to classify and evaluate the sources found. If terms such as “randomized controlled trials,” “sample size,” and “statistical significance” are not completely foreign to you, in most cases you have a good chance of completing your clinical evaluation yourself within a few weeks (excluding a clinical trial).

We definitely advise you to at least familiarize yourself with the basics of the topic – it often seems more complicated than it actually is at first. In the end, you can still decide to outsource the topic.

On the other hand, it is often worth commissioning an appropriate provider to carry out a clinical trial. They have better opportunities for recruiting study participants and are familiar with the design and implementation of such studies. Those who do not have in-depth experience in this area run the risk of making mistakes that can have serious consequences. If a study is designed incorrectly, for example, months of work could end up being in vain. Suitable providers are, for example, Clinical Research Organizations (CRO), which in most cases have a broad pool of experts in the scientific, statistical and medical fields. However, colleges and universities are also conceivable partners.

Caution: When selecting a suitable partner, you should make sure that the investigation carried out also meets the requirements for clinical trials of the MDR and the Medical Devices Implementation Act (only relevant for Germany). This applies to most CROs, whereas universities are primarily interested in gaining knowledge and publications and are not familiar with harmonized standards and laws. Discuss your plans in detail in advance to avoid any misunderstandings.

Of course, the entire clinical evaluation can also be outsourced. This is particularly helpful if you have no experience with clinical trials and regulatory requirements yourself—or if you can simply afford it and are afraid of making mistakes.

One advantage of this is that you can prove the independence of the persons involved in a very plausible way. This can help justify the clinical evidence to the outside world. Provided that no one receives a bonus if the data found matches the manufacturer’s statements as closely as possible. A founder of a health start-up, on the other hand, could be assumed to want to present his product in a good light and only include selected facts in his report.

The disadvantages, on the other hand, are the costs and the expertise that your team may lose if the search for and analysis of clinical studies is outsourced.

5. Future: The new ISO 18969

While MEDDEV 2.7/1 Revision 4 currently remains the undisputed gold standard, a new international standard is already looming on the horizon: ISO 18969 “Clinical evaluation of medical devices” The draft was published in 2025 and is now in the public comment phase.

ISO 18969 describes at an international level how clinical evaluations should be carried out systematically throughout the entire product life cycle. Among other things, it specifies more precisely which sources of evidence may be used and how clinical evaluation is to be embedded in quality management.

Our recommendation: Until the standard is finally adopted, continue to follow the MDR and MEDDEV guidelines. Nevertheless, it may be worth taking a look at the draft of ISO 18969 to get an early feel for the possible upcoming harmonization and to future-proof your process.

6. Helpful resources

MDR: Central work from which the necessity and all requirements for clinical evaluation are derived.

MEDDEV-2.7/1 revision 4: Guideline for the preparation of the clinical evaluation. Although the document was not written explicitly for the MDR, most of the content is still up to date.

ISO 18969: Draft of the upcoming international standard for the clinical evaluation of medical devices. It describes systematic implementation throughout the entire product life cycle.

MDCG 2020-5: Guideline for evaluating the similarity of two products

MDCG 2020-7: Template for a PMCF plan

MDCG 2020-8: Template for a PMCF report

Formulating the intended purpose for (software) medical devices: Guide to formulating the intended purpose for your product

Classification of software medical devices: MDR Guide: Guide to finding the risk class of your product according to MDR

Guide: Is your app a medical device?: Here you can find out whether your product is a medical device according to MDR.

7. Conclusion

The effort involved in the clinical evaluation depends enormously on the need for a clinical trial and the scope of the literature search. Although it is possible under the MDR to refer to similar products that are already on the market, this similarity requires a satisfactory explanation. For start-ups in particular, it makes a lot of sense to search the market intensively in order to identify such products. After all, clinical trials are expensive and take several months to years. The chances of finding a suitable product naturally vary from case to case, and when it comes to access to the appropriate clinical data, you have to rely on the manufacturer’s favor in cases of doubt.

Even though clinical evaluation may sound very complex and time-consuming at first, smaller companies and start-ups should not be put off by this. In many cases, it can be carried out internally and does not require external service providers. Companies can benefit greatly from this, as they generate new knowledge and the costs of clinical evaluations can be better estimated in the future. If a clinical trial is necessary, companies often turn to clinical research organizations (CROs).

If you are planning to develop medical software or a DiGA and need support with the development, please feel free to contact us and we will discuss the whole thing together without obligation. We develop medical apps and medical software for companies on a contract basis.

Any further questions? Please feel free to call us (+49 (0) 89 54998380) or send us an email (kontakt@quickbirdmedical.com).