Status 28.06.2021

That a pacemaker should be a regulated medical device is obvious. However, with software, especially apps, the ambiguity is greater. Mobile apps must also be classified as a regulated medical device if they are used for specific purposes such as the diagnosis or therapy of diseases. In fact, if you want to get your DiGA (digital health app) reimbursed under the DVG, classification as a medical device is one of the requirements.

In this article, we will give you an overview of how to decide whether your app or software is a medical device.

Subsequently, you can find the correct risk class for your app here: Classification of software medical devices: MDR Guide.

Terminology: MDR, Medical Device & CE

For the purposes of this article, the term “medical device” is defined by the definition in the Medical Device Regulation (MDR). Briefly summarized: A medical device is a product with a medical intend. In order for medical devices to be placed on the European market or put into operation, they must be CE marked. An app as a medical device is often also called a medical app or medical software.

We highlight the entire path to medical device approval (and thus CE marking) in this article: Approval & Certification of Software Medical Devices (MDR).

Motivation: App as a medical device

Most of the time, it all starts with the idea of developing an app or software that will be used in the healthcare/medical field. In the second step, the question arises whether your planned product is a medical device or not. As a software service provider, we specialize in the development of medical apps and therefore know the problem very well. This evaluation has a great impact on the future of your product. Depending on whether you launch your app as a medical device, many circumstances change. On the contra side: an app as a medical device…

- is more complex and therefore more cost-intensive

- Requires expertise in quality management, which must either be built up internally or purchased externally

On the pro side: an app as a medical device….

- can be reimbursed (more easily) by the health insurers, if necessary. Classification as a medical device is a basic requirement for inclusion in the DiGA directory under the DVG and thus for reimbursement.

- sets its own application apart from the competition, most of which will not be classified as a medical device. The CE mark builds confidence among patients, physicians, health insurers and other healthcare professionals.

However, the decision whether your own app is a medical device is only indirectly up to you. A given product with a defined purpose and functionality either falls under the definition of a medical device or not. That depends on the MDR legal text. So you have to abide by that. Otherwise, you are not acting legally (more on this below). However, to avoid classification as a medical device, you can of course change the intended purpose and functionality of the product accordingly. For example, if you first intended to develop an app to support therapy for rehab patients, you can develop a fitness app instead (which does not specifically target patients and therapy is not part of the intended purpose). Read more in our article on formulating the purpose statement.

Basically, in the past it was usually the case that companies tried to define their software/app in such a way that it was not a medical device. The effort, the costs and the necessary know-how were simply too high barriers to entry. This is currently changing radically as a result of the Digital Supply Act (DVG) and the DiGAV. In order to have a DiGA (digital health application) reimbursed by statutory health insurers under the DVG, this app/software must be classified as a medical device (of a low risk class). Therefore, more and more companies are currently asking themselves the question: “How do I ensure that my DiGA can be classified as a medical device?”. You can only legitimately classify your DiGA as a medical device in Europe if it falls within the definition of a medical device under the MDR (or MDD, prior to 05/26/2021).

Focus of the article: MDR

In this context, we focus on the European market, and specifically consider the Medical Device Regulation (MDR). Since certification as a medical device in accordance with the Medical Device Directive (MDD) is no longer possible since May 26, 2021, we will not discuss this further here. Incidentally, there is extensive overlap between MDR and MDD in the definition of a medical device. In addition, in this article we specifically consider standalone software (also called standalone software) as a medical device. This includes mobile apps in particular. We do not go into further detail on hardware (such as pacemakers).

When is my app/software officially a medical device?

Before we look at specific examples, it is important to understand what “officially” determines whether your app is a medical device. Surprisingly, this depends on only one definition in the MDR. Your app is a medical device if it falls under the MDR’s definition (“definition”) of a medical device:

“Medical device” means an instrument, apparatus, device, software, implant, reagent, material, or other article that, according to the manufacturer, is intended for human use and is intended, alone or in combination, to fulfill one or more of the following specific medical purposes:

- Diagnosis, prevention, monitoring, prediction, prognosis, treatment or alleviation of disease,

- Diagnose, monitor, treat, mitigate, or compensate for injury or disability,

- Examination, replacement, or alteration of anatomy or of a physiological or pathological process or condition,

- Obtaining information by the in vitro examination of samples derived from the human body, including organ, blood and tissue donations, and whose principal intended action in or on the human body is not achieved by pharmacological or immunological means or metabolically, but whose mode of action may be supported by such means.

The following products are also considered medical devices:

- Products used to prevent or promote conception,

- Products specifically intended for the cleaning, disinfection or sterilization of the products referred to in Article 1(4) and the products referred to in paragraph 1 of this indent.

The purpose decides

Specifically, this paragraph means, among other things, that for qualification (deciding whether your product is a medical device), it is the intended purpose that counts. The functionality of your app/software is not relevant or has only indirect influence on the purpose. If the intended purpose of your app is, for example, the therapy, diagnosis or prevention of diseases, it must be classified as a medical device. Purpose is defined by MDR as follows:

“Intended use” means the use for which a device is intended according to the manufacturer’s labeling, instructions for use, or promotional or sales materials, or the promotional or sales claims and its clinical evaluation claims;

It is also clear here that the defined intended purpose of your product must also be communicated in this way, e.g. on all marketing/sales channels. You cannot market your medical device under a different intended purpose than you have stated in the declaration of conformity. If you need help formulating the intended purpose, see this article for more information: Forumlating the intended purpose for (software) medical devices.

Let’s take the example of a diabetes app. If your app is intended for the “documentation of glucose values”, it is not a medical device. It does not serve the therapy, prevention, diagnosis, etc. of diseases. It is purely a documentation tool with no direct medical purpose. However, if your app evaluates the documented values and gives advice on this basis (“you should eat something”), “therapy recommendations” are present. The app thus has the purpose of “the therapy of diabetes”, for example. It is a medical device. The fact that the purpose is in the foreground is also made clear again in the preface (19) of the MDR:

It is necessary to clearly establish that software as such, if specifically intended by the manufacturer for one or more of the medical purposes listed in the definition of medical devices, is a medical device, while software for general purposes, even if used in healthcare facilities, and software used for lifestyle and wellness purposes is not a medical device. […]

Software/apps for general purposes, and thus not the specific application in the medical field, is not a medical device. For example, Microsoft Excel is not a medical device because it is intended for use cases of any kind. Excel can, of course, also be used to calculate certain key figures that could be used to diagnose a disease, for example. However, this is not the intended purpose of Excel. On the other hand, an app/software that specifically has the calculation of key figures for the diagnosis of a certain disease as its purpose is a medical device.

Note: It is possible that your software/app does not fall under the MDR, but under the IVDR (In-vitro Diagnostics Regulation). If your app is intended for obtaining information through the in vitro examination of samples derived from the human body, it falls under the IVDR. The qualification criteria are similar. However, this article does not explicitly cover this type of software.

What does this mean specifically?

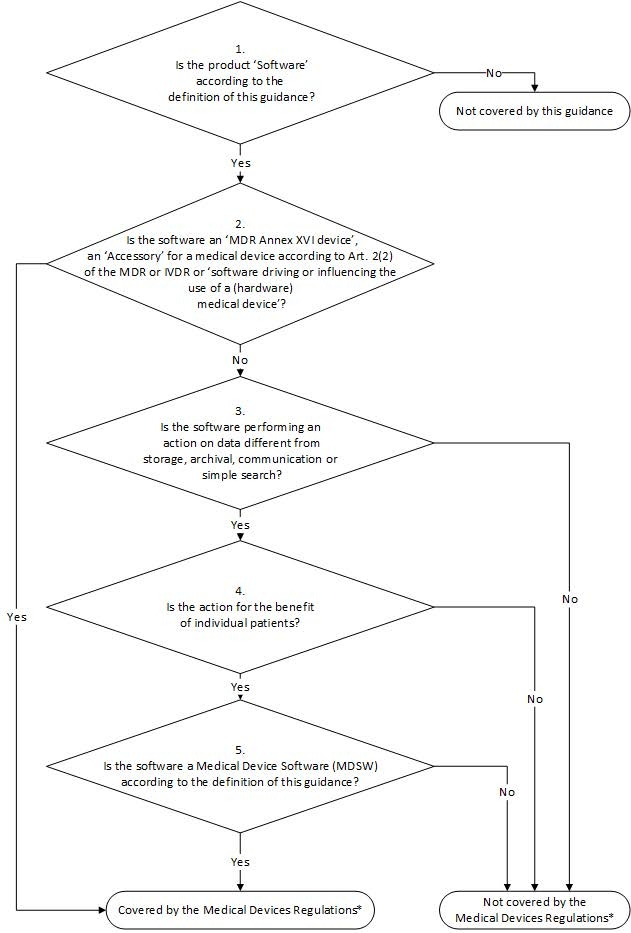

As you can see above, a single article of the MDR decides which software or devices are medical devices. So you don’t have to go through the entire MDR to make this decision. At first glance, this seems to be an advantage. Unfortunately, however, it is more of a disadvantage: the definition is very brief and thus very vague. To decide in concrete cases, a little more background knowledge and guidance is needed. Therefore, there are documents that try to explain the facts better with concrete examples. Probably the most important guidance document in the context of the MDR comes from the MDCG (Medical Device Coordination Group) and is entitled “Qualification and classification of software […]”. Within this article, we refer to this document as “MDCG Guidance” (although there are a variety of different MDCG guidance documents).

The MDCG Guidance is not legally binding, but helps interpret the MDR paragraph. What we refer to in this article as software as a medical device, the MDCG Guidance refers to as Medical Device Software (MDSW). To help you decide whether your application is an MDSW (and therefore a medical device), the MDCG Guidance includes, among other things, a decision tree:

MDCG Guidance decision tree: click to enlarge

Types of apps/software as medical devices

Within the MDR and MDCG Guidance, a distinction can be made between three different types of software/apps as a medical device (or MDSW):

1. Accessories of a medical device

If your software/app controls or influences another medical device (mostly hardware), it may be an accessory of a medical device. The MDR defines this as follows:

“Medical device accessory” means an item that, while not a medical device per se, is intended by the manufacturer to be used in conjunction with one or more specific medical devices and specifically enables its use in accordance with its intended purpose(s) […].

The controlling software is thus itself also a medical device.

2. Independent medical device

If your software/app independently has its own medical purpose, it is an independent medical device. For example, an app that provides therapy recommendations based on certain input values is an independent medical device. The majority of DiGA, for example, will fall into this category.

3. Part of a medical device

Certain software is an integral part of the medical device. Therefore, the software does not need to be reclassified independently. This primarily includes embedded software, such as the software/firmware of a blood pressure monitor. An app is unlikely to fall into this category because it runs on a smartphone, which is not itself a medical device. Depending on the type, slightly different regulations apply under the MDR, which we will not go into here.

Frequent uncertainties

When evaluating whether a medical device is present, there are some typical ambiguities. We resolve some of them here:

Communication & Data Storage:

A chat or video call solution is usually not a medical device. The purpose is pure communication. This also applies, for example, to pure data storage/documentation. The MDCG guideline clearly states that “storage, archiving, communication & simple search is not a medical device”.

Influence of the operating system, runtime environment and “whereabouts” of the software:

Whether your software runs on a remote server, whether it runs on your smartphone, whether it runs on Android or Windows, none of this has any bearing on whether it is a medical device. As described above: the intended purpose counts.

Potential patient risk:

The risk with which your app/software causes harm to a patient is not relevant. The probability and severity of a possible medical harm have no influence on whether your app is a medical device. The following argumentation is not purposeful: “Our app can only cause a very small harm after all. Therefore, it should not be a medical device.” If, for example, the purpose is nevertheless the therapy of a disease, we continue to talk about a medical device.

Indirect vs. direct damage:

It is often assumed that certain apps are not a medical device because they “only provide decision support” for the doctor or patient. In the end, it is still the doctor or patient who decides how to act. Therefore, it should not be a medical device? This argumentation is also not purposeful. If your app gives therapy recommendations, the medical purpose is the “therapy of a disease” and therefore a medical device. And that’s right: an overworked doctor or tired patient tends to trust their software tool more and more. Certain recommendations may no longer be questioned, and thus potentially wrong decisions with serious consequences could be made. Insofar as they are intended for the therapy of diabetes, the following products are thus equally medical devices: a physical insulin pump, an app for controlling an insulin pump, or even just an app that gives specific dose recommendations for injecting insulin.

User of the software: patient, doctor or a ” non-professional”:

Just because your app isn’t used by a doctor or patient doesn’t mean it isn’t a medical device. For example, a mother might help her child with limited mobility to treat an illness. The mother may be using software to do this. However, she has no medical training and is not a patient herself. Nevertheless, the purpose is therapy. Thus, there is a risk that the therapy is performed incorrectly, and thus the application is also morally rightly a medical device.

Comparison with other apps on the market

People also often try to argue by comparing our app with other apps on the market: “App XY is in the App Store, has the same functionality as our app, and is not a medical device. Why do we have to be a medical device then?” The comparison with other apps does not help here either. There are many apps on the market that should be classified as medical devices, but are not. However, no conclusions can be drawn from this for your own app. Often, the manufacturers of such apps have acted out of sheer ignorance. However, in the event of a lawsuit/reminder, they are vulnerable. If you want to build a stable business with your app, you should comply with the legislation.

Who makes the final decision?

You must decide for yourself whether your software is a medical device. To do this, you can consult the BfArM, consultants, lawyers or even notified bodies. In the end, however, the decision is still yours. In case of a lawsuit, your decision will be reviewed by the court.

If, for example, you have mistakenly not marketed your software as a medical device, you will bear the consequences. A review by a judge can be triggered, for example, by a case of damage. A patient or the competition could sue you or send a warning letter. So if you are unsure, it is worthwhile to obtain an assessment or an expert opinion from a third party.

The following options are available for this purpose:

- inquire at the BfArM (however, the long response times here are usually not sufficient)

- have an expert opinion issued by a lawyer specializing in this field

- Obtain an assessment or opinion from a regulatory consultant

It is important to emphasize again that even these assessments and opinions do not automatically protect you legally. In the event of a lawsuit, for example, a lawyer would still have to defend you in court based on this expert opinion. However, there is a good chance that you will win the case if your attorney has done a diligent job.

Current market situation: reimbursement of DiGA

The number of apps that have made it onto the market as medical products is still manageable. On the one hand, this is due to the effort required to develop an app as a medical product. On the other hand, it has been difficult to build a functioning business model with the finished app/software. The new DVG at least makes it easier to build a business model by allowing certain software or DiGA to be reimbursed by health insurers in a standardized way. Reimbursement for digital personal care applications (DiPA) is also expected to become law in 2021. Unlike DiGA, DiPAs are not defined as medical devices. You can read more about this in this article.

Within the framework of the DVG, the Spitzenverband Digitale Gesundheitsversorgung has already published a list of members submitting digital health applications in advance. According to the requirements of the DiGAV, these are all medical devices. Here you can get a good impression of the applications that will be available on the market in the future with CE marking.

Conclusion

It is not always easy to decide whether your app/software is a medical device. The definition of the MDR gives only very vague guidelines. The MDCG Guidance tries to provide a better understanding with illustrative examples. However, in case of doubt, it is always advisable to ask for a third opinion. If you additionally want to know whether your app qualifies not only as a medical device, but also in which risk class it falls, it is worth taking a look at our article “Classification of software medical devices: MDR Guide”.

Apps in low risk classes may even qualify as DiGA. Learn more in our article “Is Your App a DiGA?”.

We develop medical apps and medical software on a contract basis for our customers. Therefore, we are regularly confronted with the question addressed. For a free initial assessment of whether your app/software is a medical device, please feel free to contact us at any time.