“The use of my app is completely safe. It certainly falls into the lowest risk category.”– MDR probably sees it differently. Anyone who wants to certify their software as a medical device in accordance with the Medical Device Regulation (MDR) must deal intensively with the question of the risk class. It is not for nothing that the MDR even defines a separate rule for software medical devices. An incorrect classification can lead to considerable additional work and legal consequences. For this reason, our guide supports you in this complex topic. In the following, we guide you through the decision process for the MDR classification of your software. We will help you find the right class.

Update – June 2025: In June 2025, the official guidance document “MDCG 2019-11: Guidance on Qualification and Classification of Software […]” was amended in Revision 1. All changes are fully taken into account in this article. A detailed list of all changes can be found in the chapter below: Link to chapter.

Update – December 2025: In December 2025, the European Commission presented a draft amendment to the MDR, which, among other things, affects Rule 11 on the classification of software medical devices. The potential consequences for Class I software are outlined in Chapter 9 of this article.

- 1. Is your app a medical device?

- 2. MDR risk classification: briefly and concisely

- 3. The purpose decides

- 4. Which risk class does my app belong to?

- 5. Who makes the final decision?

- 6. Effects of risk classification

- 7. Risk class I, IIa IIb = DiGA?

- 8. Update of the official MDCG Guidance (Revision 1) – June 2025

- 9. Draft Amendment to the MDR (December 2025): Impact on the Classification of Software

- 10. Software under MDR vs. IVDR

- 11. Conclusion

1. Is your app a medical device?

The intended purpose determines whether your app should be classified as a medical device at all. Only if this is the case, you can deal with the risk classification. Article 2 (1) of the MDR clearly defines which products are to be classified as medical devices. For example, an app for analyzing cardiac performance can either be intended as a fitness tracker or support a cardiologist in diagnostics. Only in the second case is the app considered a medical device. As a manufacturer, you decide yourself what purpose your software has. You want to know whether your software is a medical device? Then you will receive in our guide for a more detailed overview: to the guide.

2. MDR risk classification: briefly and concisely

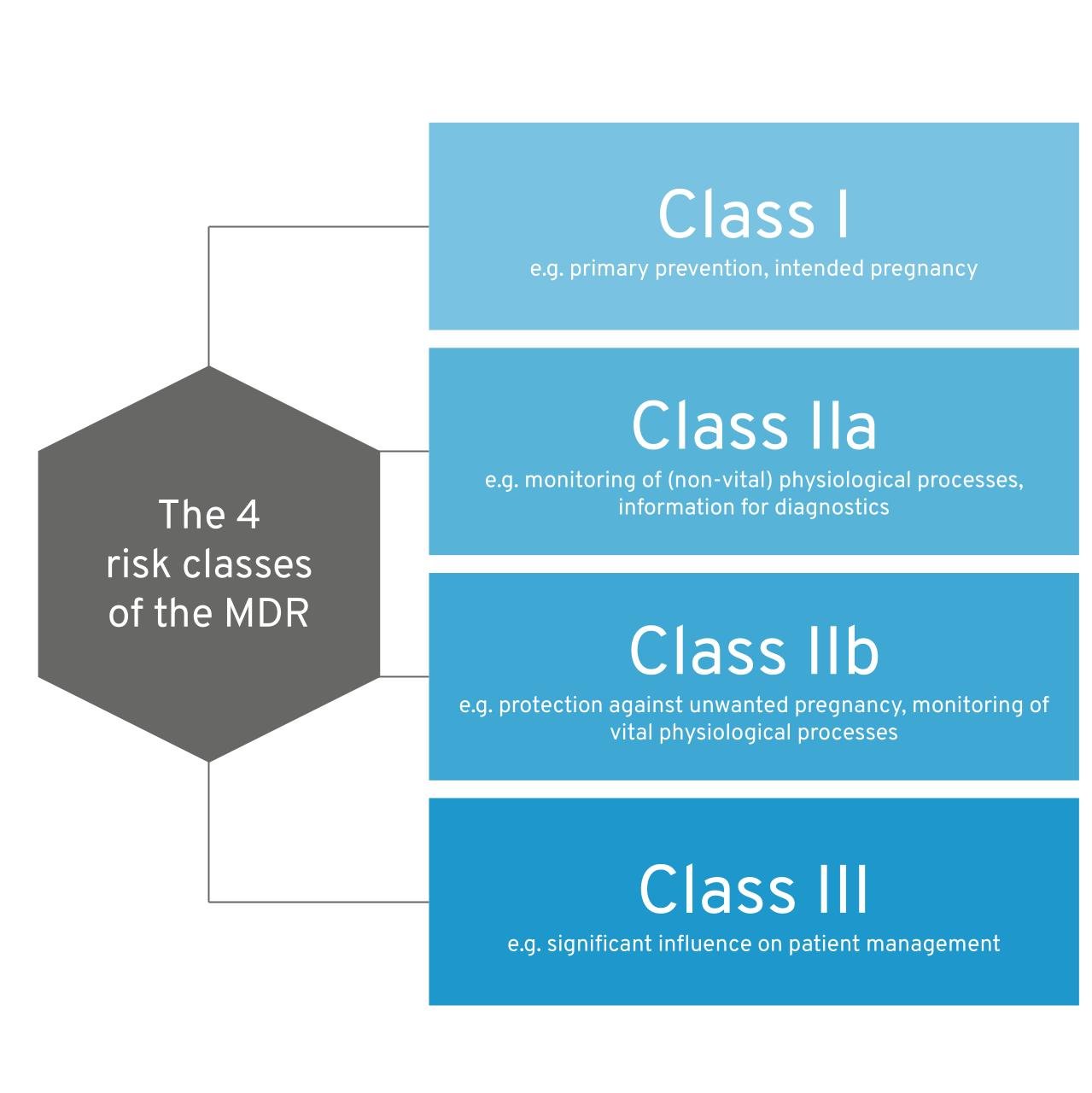

The bottom line of the MDR classification rules in a nutshell: The MDR differentiates between 4 risk classes: I, IIa, IIb III  Figure 1: The four risk classes of the MDR. As a rule of thumb, the greater the potential harm caused by the use of medical device software, the higher the class tends to be. As soon as your software influences decisions about a patient’s therapy and diagnosis, or monitors physiological processes (e.g., sleep patterns), it already falls into at least class IIa (rule 11). If a patient is in grave danger, the risk class increases further (e.g. your app provides support after a heart attack). Software that monitors vital parameters (heart, lungs, etc.) also falls into a higher class. As soon as several rules apply to your software, the strictest rule (the highest risk class) applies. The MDCG guidance document provides a particularly helpful supplement to this guide.

Figure 1: The four risk classes of the MDR. As a rule of thumb, the greater the potential harm caused by the use of medical device software, the higher the class tends to be. As soon as your software influences decisions about a patient’s therapy and diagnosis, or monitors physiological processes (e.g., sleep patterns), it already falls into at least class IIa (rule 11). If a patient is in grave danger, the risk class increases further (e.g. your app provides support after a heart attack). Software that monitors vital parameters (heart, lungs, etc.) also falls into a higher class. As soon as several rules apply to your software, the strictest rule (the highest risk class) applies. The MDCG guidance document provides a particularly helpful supplement to this guide.

3. The purpose decides

Let’s start with an example that illustrates the impact that medical purpose has on the risk class.

- Your app monitors a woman’s cycle to increase the likelihood of a wanted pregnancy. – Risk Class I

- Your app monitors a woman’s cycle to reduce the risk of unwanted pregnancy. – Risik Class IIb

An increase of two risk classes, even if it is one and the same product? Yes, in fact, purpose makes an immense difference. Accordingly, you should first think carefully about what the intended purpose of your app should be. You may well adjust your purpose after you finish reading this article. Our article on intended use describes the exact contents and helps you with the wording. You can find out whether your app is a medical device at all in this article.

3.1 Standalone, control software, and accessories

Any Software with a distinct medical purpose is classified separately. Overall, there are three different types of software that we would like to distinguish at the outset:

- Standalone software / Standalone software

- Software used in conjunction with another medical device

- Software as part of a medical device

Important at this point for you is that you do not have to classify your software separately if

- they are an integral part of another medical device (e.g., embedded software, such as firmware of a blood pressure monitor). This is almost never true for mobile apps.

- they exclusively serves to control another medical device (e.g. UI for operating a defibrillator). Then it automatically falls into the same class as the controlled product. However, if the software has another purpose, you must check whether it falls into a higher class.

In all other cases, you need to find the right class for your software. Learn more about the types of software as a medical device here.

4 Which risk class does my app belong to?

As mentioned earlier, the intended purpose of your app provides the basis for determining which of the four risk classes it falls into. Once the intended purpose is clear, use the rules in Annex VIII to the MDR to find the right class for your software. We recommend starting the search for the class at rule 11, as this specifically addresses software. At the same time, it is worth taking a look at the MDCG guidance document. Its core contents are summarized in this article.

4.1 The rule 11 of the MDR

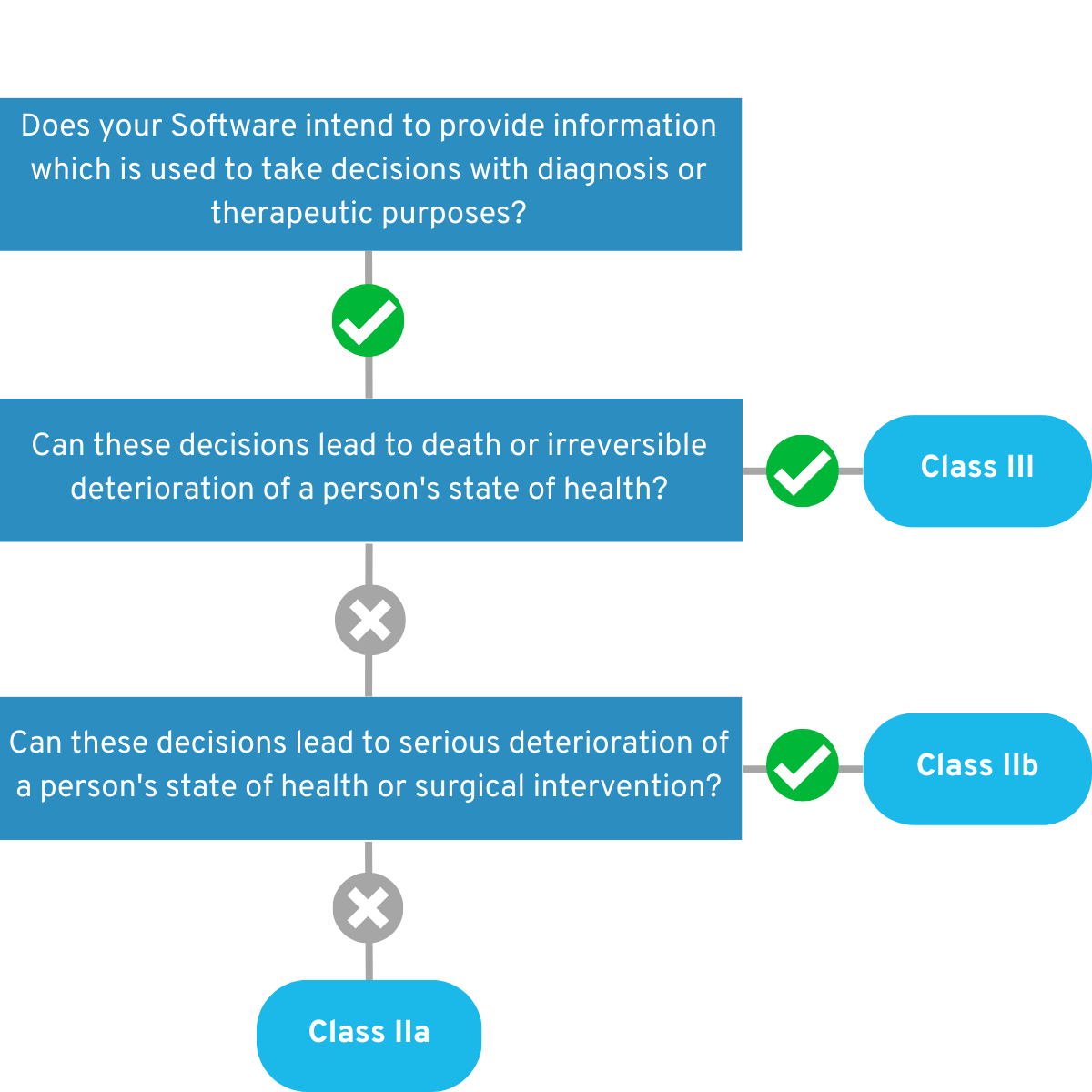

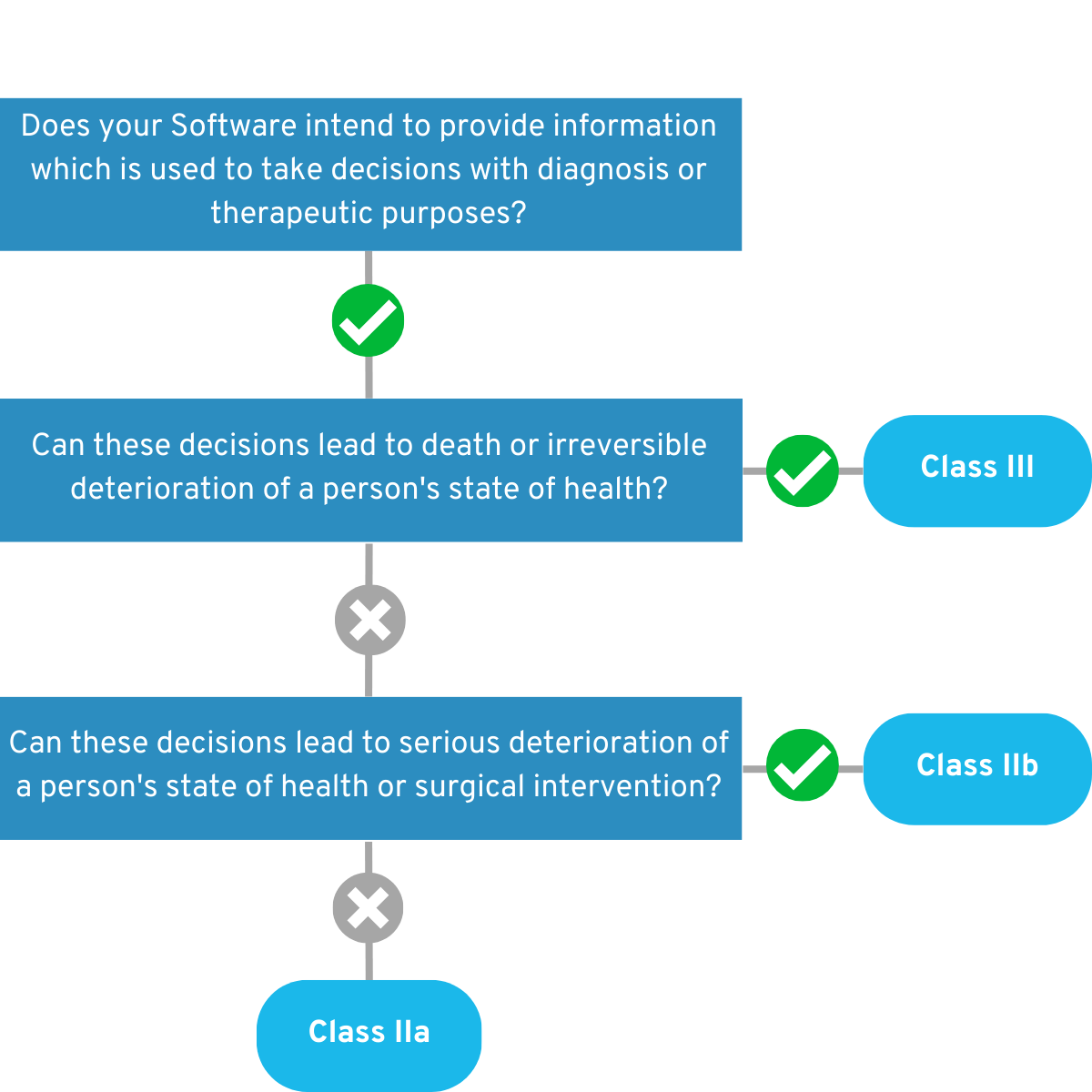

For medical software, Rule 11 is decisive in most cases. Here, a distinction is made between software that Provides information for therapy and diagnostic decisions and monitors physiological processes. An app can, of course, serve multiple purposes. According to Rule 11, you must make the following decisions:

4.1.1 Is your app intended to provide information that will be used to make diagnostic or therapeutic decisions?

If so, answer these questions below: Can these decisions cause death or irreversible deterioration of health? If so, your app falls into the Risk Class III. 💡 Example:

Their software uses image analysis to provide the basis for an emergency physician’s decision on how to treat a patient with an acute stroke.

Can these decisions cause serious deterioration of health or surgical intervention? If this is true, your app falls into the Risk Class IIb. Example:

Your app provides the basis for a physiotherapist to decide at what point an injured knee can be loaded again. Overloading could lead to surgery.

If you can answer “No” to both questions, your app falls into risk class IIa for the time being. Example:

Their app uses questionnaires to measure the severity of ADHD symptomatology in adults.

Figure 2: Graphical representation of the decision tree of the first part of Rule 11.

Figure 2: Graphical representation of the decision tree of the first part of Rule 11.

4.1.2 Is your app intended for monitoring physiological processes?

If yes, answer these questions below: Is the app intended to monitor vital physiological processes (heart, lung, brain function, etc.), where the nature of the change in these parameters may result in immediate danger to the patient? If so, your app falls for the time being into the Risk Class IIb. Example:

Your app monitors a person’s heart rate while they are in a coma. In the event of health-critical readings, medical personnel are alerted so that they can intervene in good time.

If you can answer “No” to this question, your app will initially fall into risk class IIa. 💡 Example:

Their app monitors a patient’s sleep patterns at home to measure the success of sleep disorder therapy.

Figure 3: Graphical representation of the decision tree of the second part of Rule 11.

Figure 3: Graphical representation of the decision tree of the second part of Rule 11.

4.1.3 Does your app have another purpose?

Rule 11 clearly states in the last sentence: “All other software is assigned to Class I.” So you have your answer for this case as well – or do you? Unfortunately no, because then the question arises whether another rule can be applied to your app. Rules 15 and 22 are particularly relevant here:

- Rule 15 addresses active devices used for contraception or protection against sexually transmitted diseases. Software in this area falls within Class IIb.

💡 Example:

Your mobile app is intended for contraception. To do this, it reminds a user to take the contraceptive pill every day. If the intake has not been confirmed by a certain time, the app generates a warning signal.

- Rule 22 addresses active therapeutic devices with integrated or built-in diagnostic function that significantly determines patient management by the device, such as closed-loop control systems or automated external defibrillators. Software in this area falls within Class III.

💡 Example:

Your software is intended for further accompaniment after psychotherapeutic treatment of depression. Through the built-in diagnostic function, the software adjusts the treatment and determines the need for renewed psychotherapy.

Important: If your software falls into risk class IIb or lower according to Rule 11, you need to look at all the other rules – because there may be a stricter one that increases the risk class. If several classification rules can be applied to your software, the strictest rule is always applicable!

4.2 What else falls into Class I anyway?

There is indeed a gray area when it comes to interpreting Rule 11 in the MDR. We provide detailed guidance on this topic in our guide: Class I software according to MDR – is this still possible at present?

4.3 Case studies for determining the risk class

These case studies are intended to illustrate the decision-making process. They are fictitious examples.

4.3.1 Case study 1: App to accompany exposure therapy

Your app is intended to accompany the exposure therapy of a patient with fear of heights. For this purpose, a list of situations that scare the patient (e.g., standing on the balcony of his apartment for 5 minutes.) is developed together with his therapist. These situations are ordered from “not very scary” to “very scary”. Now he is to try independently at home to seek out and endure one of these situations. Afterwards, the app uses a questionnaire to record how the patient felt in the situation. Based on this data, the therapist decides on a weekly basis when is the right time to increase the level of difficulty.  We start with rule 11:

We start with rule 11:

- The app provides information that influences therapeutic decisions. We could argue that neither death nor irreversible or serious harm can result from these decisions. Accordingly, the product would be classified as class IIa.

Since no other rule applies, the app remains in Class IIa. It could also possibly be argued that therapy recommendations could place the patient in a hazardous situation that could cause death (e.g., a steep cliff of a mountain). Thus, the product would fall into Class III. However, we explicitly decide not to make such recommendations in the app here. However, this shows well the scope for argumentation in the classification of a medical device.

4.3.2 Case study 2: App for therapy after a heart attack

You have developed an app that monitors a patient’s cardiac performance at home after a heart attack, once treatment has been completed. Based on the readings, the app informs the patient when it is necessary to take a vital medication and when to return for follow-up care.  We start with rule 11:

We start with rule 11:

- The app monitors vital physiological processes (cardiac output). Accordingly, the app would be a Class IIb medical device.

We also need to look at the other rules to see if a stricter rule needs to be applied as well. In Rule 22, we see:

- Your app adapts the therapy and decides for itself which therapeutic measures are necessary. In this way, it influences patient management.

Therefore, your product would fall into risk class III, because the strictest rule is always applied. Caution: With both examples, it would certainly be possible to spend an entire afternoon discussing whether these assessments are ultimately correct. It is important for us here to give you some tangible examples for further understanding. A crystal clear classification into one class is not always possible, because the law can be interpreted in different ways. So there is room for argumentation. Therefore, enjoy these assessments with caution.

5. Who makes the final decision?

You. The decision as to whether software is a medical device is made by the manufacturer. The manufacturer also determines the risk class classification. However, you should proceed with caution, as the notified body can prevent certification if it does not agree with your risk classification. Find out more about medical device certification here: Approval & certification of software medical devices (MDR) If your product has been assigned to risk class I, you do not need a notified body, but the assigned supervisory authority can still point out any incorrect classification and potentially require you to subsequently withdraw your product from the market. If you are unsure, it is best to get an expert opinion or third party assessment. The options for this are:

- A specialized lawyer who will give you an expert opinion

- A regulatory consultant who provides an assessment

- the BfArM (unfortunately long response times and therefore hardly practicable)

Note: Neither an expert assessment, nor an expert opinion protects you legally! However, such documents can be decisive in the event of later legal proceedings.

6. Effects of risk classification

The risk classification of medical devices has a decisive influence on regulatory requirements and the effort involved in approval and market surveillance. The transition from Class I to Class IIa is particularly critical in this regard, as the higher classification entails significant additional requirements. While Class I products are subject to self-certification by the manufacturer, Class IIa requires the involvement of a notified body, which significantly increases documentation requirements, testing procedures, and costs. Precise and compliant risk classification is therefore essential to minimize regulatory risks and avoid delays in market access. You can find out exactly what to expect with a risk class IIa product compared to class I in a separate technical article we have published: MDR risk class I vs. IIa: Differences for software medical devices

7. Risk class I, IIa IIb = DiGA?

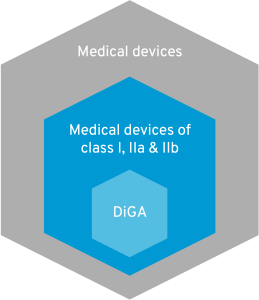

A Digital Health Application (DiGA) is an app that is prescribed by doctors and psychotherapists and whose costs are covered by statutory health insurance. For an app to be a DiGA, it must fall into risk class I, IIa or IIb. Does that mean that all apps in these risk classes are automatically DiGA? No! To be included in the DiGA directory, apps must fulfill a thick catalog of requirements. DiGA should optimize care or create structural facilitation for patients. Apps whose users are primarily physicians, for example, are already excluded.  In addition, DiGA must not represent pure primary prevention. However, since risk class I predominantly covers such offers, this is another reason why many apps are exempt from the DiGA regulation. All criteria for a DiGA can be found in this article. Digital medical devices that are currently excluded from the DiGA definition in Germany due to risk class III are now being given a chance in France. You can find out all about DiGA in France in this blog article.

In addition, DiGA must not represent pure primary prevention. However, since risk class I predominantly covers such offers, this is another reason why many apps are exempt from the DiGA regulation. All criteria for a DiGA can be found in this article. Digital medical devices that are currently excluded from the DiGA definition in Germany due to risk class III are now being given a chance in France. You can find out all about DiGA in France in this blog article.

8. Update of the official MDCG Guidance (Revision 1) – June 2025

In June 2025, a long-awaited update to the official MDCG guidance document on risk classification and qualification was implemented in the digital health scene. Until now, the MDCG guidance has been rather vague, for example with regard to patient-oriented exercise software (the majority of DiGA listed in the BfArM directory). There was a relevant gray area in the interpretation of Rule 11 with regard to classification in risk class I vs. IIa. For a long time, there were fears that the update could eliminate the possibility of a risk class I for software medical devices.

All clear: Fortunately, this did not happen. The new guidance document is still just as vague when it comes to risk class I vs. IIa, for example in the case of patient-oriented software such as DiGA.

QuickBird Medical’s personal opinion: The fact that risk class I has not been explicitly excluded for patient training apps is good news. Restricting it would have been a serious mistake. It would have severely hampered European innovation in the field of digital health applications. The risks associated with medical devices must always be assessed in relation to their benefits. Daher braucht es weiterhin Möglichkeiten, Apps unter Risikoklasse I zuzulassen. This is the only way that small businesses can bring innovations to market that pose little or no risk. The costs and expenses of a Risk Class IIa product are hardly affordable for many young companies. Now back to the guidance: So what has actually changed?

Specific changes in Revision 1 in June 2025: Not much has actually happened in terms of risk classification. Here is a summary of the relevant changes:

- New example for MDR Rule 11: A new example has been added regarding the classification decision under Rule 11 of the MDR: ” […] a product intended to prevent the risk of diseases or pathologies by analyzing physiological parameters (e.g., position of the vertebrae, analysis of arterial stiffness, etc.) may be considered a product that provides information used for decision-making for diagnostic purposes (possible detection of pathologies) and, in this case, falls under Class IIa. ” This clarification affects only a fraction of the software or apps on the market and changes little or nothing, for example, in the area of DiGA.

- New reference to MDCG guidance (hardware-software combinations): There are several references to “MDCG 2023-4 Medical Device Software (MDSW) – Hardware combinations” in relation to software-hardware combinations. However, this guidance does not contain any content that is directly relevant to risk classification.

- New reference to MDCG guidance (general classification): Reference is made to “MDCG 2021-24 for the general principles of medical device classification,” which deals with general classification rules. This applies regardless of whether your product is software or not. This does not change anything fundamental for the time being.

- New information on modularization: The chapter on “Modules” has been expanded to include additional information. This could be relevant for you if you need guidance on dividing software into medical device and non-medical device components.

- MDSW replaces standalone software: The term “standalone software” has been replaced with the term “medical device software (MDSW)”. This is explained by the fact that the location of the software (embedded, on a platform, in the cloud, etc.) is not relevant for classification.

That’s it. In general, these additions result in hardly any changes with regard to the Medical Device Software (MDSW) classification.

9. Draft Amendment to the MDR (December 2025): Impact on the Classification of Software

On December 16, 2025, the European Commission presented a draft amendment to the Medical Device Regulation (MDR). A key focus of this proposal is a revision of Rule 11, which is decisive for the risk classification of software medical devices.

At first glance, the new draft appears positive and suggests that software will generally be assigned to risk class I in the future, as long as no explicit criteria for a higher classification are met. However, this seemingly manufacturer-friendly system is put into perspective upon closer examination: depending on the interpretation, the draft could lead to the majority of medical software being classified as at least Class IIa – even if the risk is comparatively low.

We have summarized an in-depth analysis of the draft, the proposed version of Rule 11, and the resulting scope for interpretation in a separate article. In it, we highlight the specific consequences for software products in particular: To the technical article

Important for manufacturers: The published text is not a final legal version, but an early step in the European legislative process. Experience shows that such drafts are further revised as the process progresses. Accordingly, it cannot currently be assumed that the proposed regulation will be incorporated into the final version of the MDR unchanged.

10. Software under MDR vs. IVDR

If your product makes diagnostic decisions based on laboratory samples, for example, it may not fall under the MDR, but rather the IVDR (In Vitro Diagnostic Medical Devices Regulation). Completely different classification rules apply here. For more information on the qualification and classification of IVDR software, please refer to our guide: IVDR Software: Qualification and Classification

11. Conclusion

To find the right risk class for your app, it is best to start with rule 11 of the MDR. If your app does not fall into risk class III according to this rule, you should check all other rules again to find out whether a stricter rule should be applied to your product. In addition, it is worth taking a look at the MDCG’s Guidance document to get a feel for the classification of medical software based on further examples. It is important to know that you, as the manufacturer, make the final decision on the question of the risk class of your product. Be aware of this responsibility and also seek opinions from experts. If you are planning a medical app, DiGA or DiPA and need support with development, please feel free to contact us and we will discuss the whole thing together without obligation. We develop medical apps for companies and research institutions on a contract basis. Further questions? Please feel free to call us (+49 (0) 89 54998380) or send us an e-mail (kontakt@quickbirdmedical.com). We look forward to hearing from you!